‘I wish you are happy forever’

a story for the 10th anniversary of 9/11

Originally published Sept. 8, 2011, in The Washington Post

Eric knows what’s in his mother’s locket now, so he’s asking the kind of questions 4-year-olds ask.

“Where are they?”

“They died.”

“Why did they die?”

“Their plane was taken by some bad people,” his mother says.

“Why?” Eric asks.

The question hangs in the air as his mother considers what to tell him about her parents, whose photo is tucked into the gold heart-shaped locket. She could tell him that they came from Beijing 11 years ago to visit her in Baltimore for a year. She could tell him that they went on a trip to Maine in early September 2001 because it was cooler up there. That they boiled lobster in a cozy cottage. That they drove back to Maryland on Sept. 9 and were due to fly home to China on Sept. 10 on American Airlines Flight 77. That she thought her parents could use a day of rest before embarking on another long journey. That she called the airline and re-booked them on the same flight one day later.

But even if she told him all this, he’d probably still ask the question. Just as she has, and always will.

Why?

Death, under a microscope, is colors and shapes.

Endangered bone marrow cells are a cloud of navy dots. The cells of Hodgkin’s lymphoma are purple pairs of owl’s eyes. Zoom in to see the building blocks of an abnormality. Zoom out to see the architecture of the pathology, the whole picture. Every day, through twin lenses, Rui Zheng views mortality at the cellular level and looks for patterns in its geometry.

The microscope rests on her plain desk in a windowless office on the second floor of a building in the Johns Hopkins cancer center in Baltimore.

“Hemepath,” she says into the department phone when it rings.

Hematopathology is the study of blood diseases, the pathologies that afflict our essence. This is her specialty.

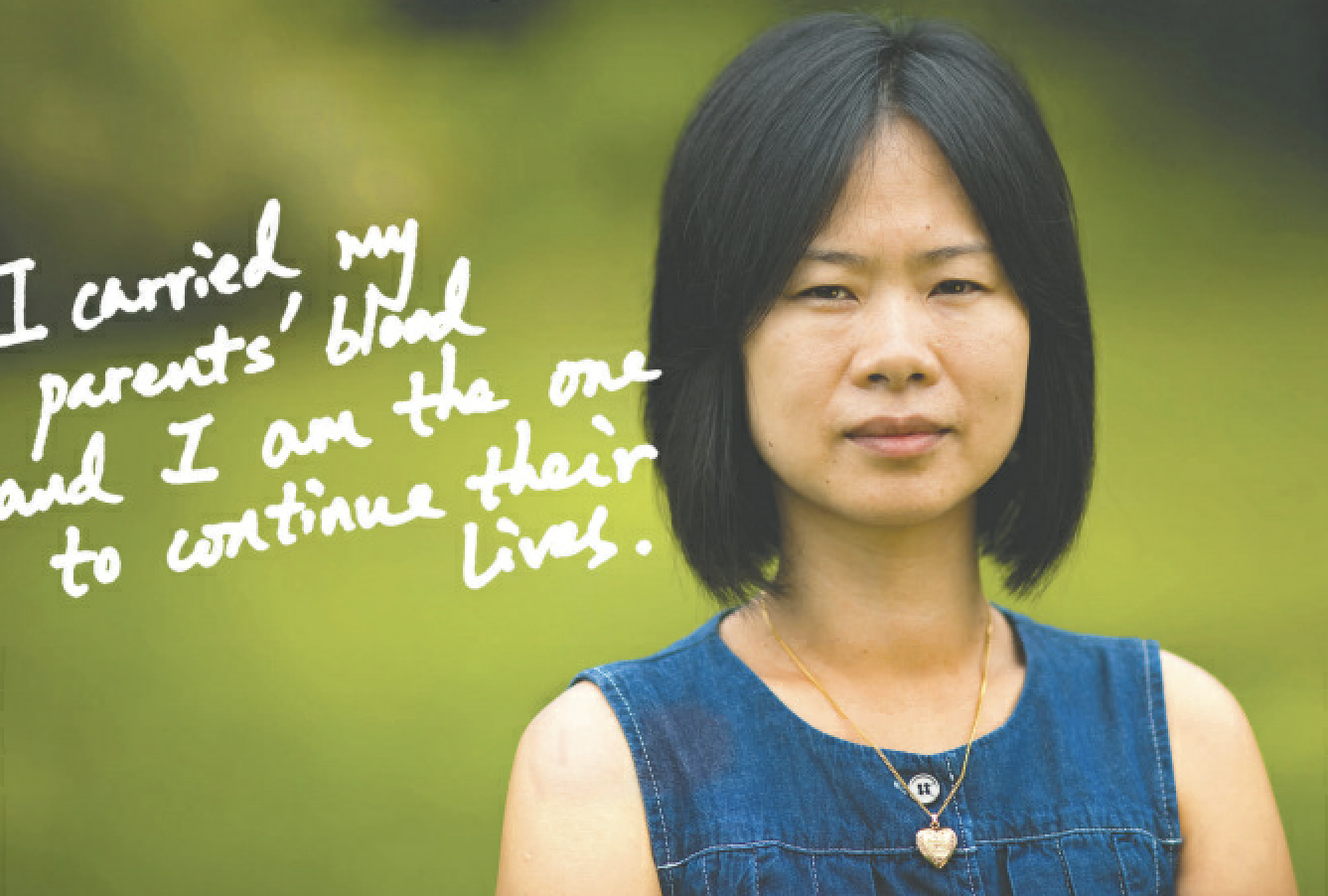

Rui (pronounced “Ray”) speaks to colleagues in a stream of jargon and acronyms. She is petite, diligent, youthful, quiet. A hemepath research fellow, a walking oncology textbook. A private person. Stoic but blunt, in virtuosic control of her temperament, the exchange student you might’ve known in high school — the one who grasped English as a second language better than you did as a first.

She’s up at 6 a.m. every weekday to the trill of her iPhone alarm. Skips breakfast. Kisses Eric before her husband takes him to summer camp or school. Listens to NPR as she drives south on I-83 through Baltimore to her microscope at Hopkins, where she has worked since she came to the United States in 1999. Then, depending on the day, she attends lectures or grand rounds, or conferences with physicians.

The goal: to help identify, understand, treat and ultimately defeat life-threatening abnormalities. Patient data flow across her desk every day and keep her at the hospital until 8 or 9 at night.

She was a college student by 16 in Beijing, then swiftly obtained a medical degree and a PhD in hematology and oncology. Science runs in the family. Her father was a chemist (and a violinist, painter and man of few words). Her mother was a pediatrician (and an excellent cook, easygoing and lively).

Rui and her parents were close. Closer, she says, than more traditional Chinese families, in which boundaries between parents and children are more defined.

She was sad to leave them, but she wanted to go abroad for her post-doctoral work, to study tumor genesis at Johns Hopkins. In August 1999, she boarded a plane bound for the United States, intending to stay for a year or two.

Her world in 2011 is sheet pizzas and B-cells, juice boxes and lymph nodes. Her world is the world of a 4-year-old who can’t sit still, of a researcher with two hospital pagers, of being a wife who lives in a suburb north of Baltimore in a red-brick subdivision, where on a late July day like this, the only sounds come from garage doors and air-conditioning units.

A sun-bleached holiday wreath is still on the front door of the house with the burgundy shutters.

Inside is a family of five. There is Rui, her husband, Li, and their son, Eric, who is clever enough to say he wants to be a trick-or-treater when he grows up, and Li’s parents, Qing and Zehua, who moved from Beijing to live with the family when Eric was born.

The house is spacious. The furnishings are spare. The den is a shrine to Eric’s toys. The living room walls are mostly naked, except for a strip of construction paper that measures Eric’s ever-changing height. Picture hangers from the previous owners are still stuck in the wall, unused.

In the kitchen, Rui presents Eric with two footwear options for today, a busy Sunday.

“A few days ago, he said, ‘Mommy’s bossy,’ but he learned that word from ‘Thomas the Tank Engine,’” Rui says, pulling socks onto Eric’s wiggling feet. “Eric, do you think ‘bossy’ is a good word or a bad word?”

“Bad word,” says Eric, playing with a wind-up toy hamster.

“Okay,” says Rui, slinging a purse over her shoulder as Li hunts for the car keys.

From the den, Li’s parents observe the scene with bright eyes and crinkled smiles. Just beyond them, resting on a fireplace mantle, is a photograph of Rui’s parents in front of the White House.

Eric has two birthday parties to attend today. But first: Wegman’s, one of his favorite places, a feast for the senses. In a bright blue polo shirt and flip-flops, he pulls his mother through the aisles.

Cucumbers, cherries, tomatoes.

Wegman’s can be a tricky place.

Lettuce, cabbage, clementines.

There are plenty of 60-year-old women pushing grocery carts.

Yogurt, pork, chocolate milk.

Sometimes, from the back, these women appear to be her mother.

Eric pulls Rui by the hand, asking “What is this?” and “What is that?” and “Can we get this?”

Eric draws squares and triangles through the condensation on the frozen-food cases.

Eric marvels at the toy train chugging its way through an elevated track near the meat counter.

“I’m Eric!” Eric says to the cashier upon checkout. Rui brushes his shiny black hair.

“Hi, Eric,” the cashier says. “How old are you?”

“Where do you live?” Eric asks.

The adults share a laugh. Kids.

Death, on national TV, is colors and shapes.

It is silver wingtips, a limestone pentagon, curlicues of orange, columns of black, blazing infographics. On, Sept. 11, 2001, Rui Zheng viewed death on a national level from the television in her brother-in-law’s basement in Virginia, where she and Li had stopped on the way back from accompanying her parents to gate D26 at Dulles international airport. There, she watched the news identify American Airlines Flight 77 as the third crashed jet.

Words fail, but they’re all she has: “Disbelief. ... Collapsed. ... The end of the world.”

This much is known about the events that occurred on Flight 77: The plane — a Boeing 757 carrying 53 passengers, two pilots, four flight attendants and five hijackers — took off from Dulles at 8:20 a.m. The hijacking began between 8:51 and 8:54 at 35,000 feet. The passengers were herded to the back of the plane. Sometime between 9:12 and 9:26, two passengers made calls to the ground and reported sharp weapons and an advancing view of suburbia out the windows. At 9:34, the passengers felt a 330-degree turn and then a roller coaster descent as the plane dove below 2,200 feet at maximum throttle. At 9:37:46, everyone on board was killed on impact.

The details are left to the imagination. Her parents were the only Chinese citizens on the flight. They didn’t speak English. Did they know what was happening? Did anyone help them, comfort them? That they were together was both a consolation and a cruelty.

For the first sleepless weeks, cocooned in her brother-in-law’s house, Rui was dogged by the phantom feeling that her parents were looking for her, wanting to be picked up from somewhere. She had dreams that they were still living at her apartment in Baltimore, waiting for her to return from a long day in the lab. At some point in the dream, Rui would come to a realization.

“I know what happened to you,” she’d tell her mother, who’d usher Rui’s father into another room, return to Rui, and reply, “We don’t want you to be sad.”

And the dream would end.

She tried counseling. It wasn’t for her. Everyone declared that her parents didn’t suffer, that their deaths were immediate, and her pedigreed logic would kick in. If it was instant, why was her mother’s handkerchief found almost entirely intact? Why was her father’s passport barely scratched?

Within a month, Rui went back to the lab to focus on answerable questions beneath the microscope. Li closed his software design company in Beijing and came to live with her. They decided to stay in the United States, partly because the concept of home was suddenly malleable.

She and Li built a new life. They became citizens, homeowners, parents.

Ten years later, holidays hurt but dreams about her parents are less frequent. When they do occur, they take place in the past, during Rui’s childhood. They are memories, not magical thoughts. She reserves magical thinking for when Eric goes to his bedroom window at night to vocalize his wishes to the universe, as 4-year-olds do.

"I wish that I listen to Mommy," he'll sometimes say, and she'll watch him and offer a silent, parallel prayer: I wish you are happy forever.

Birthday No. 1.

Jesse, a friend of Eric’s from summer camp, is celebrating his fifth birthday at the B&O Railroad Museum in Baltimore. Twenty children parade their parents under a huge rotunda dripping with giant American flags and board a train on the first commercial mile of railroad track ever laid in the country

Eric loves trains. Eric sits facing three of his fellow partygoers and introduces himself.

Rui watches from a seat across the aisle. The children squeal as the train lurches to life. Childhood birthdays were simpler in China. Hers were celebrated with Mom’s cooking and maybe a new dress. No pomp. A typical weekend outing was a trip to the library with her father.

Birthday No. 2.

Jason, a friend of Eric’s from day care, is having his fifth-birthday party at a children’s fitness center in Timonium, Md. The kids knock themselves around in a fun house of soft edges. “Ain’t No Mountain High Enough” plays over the stereo. Eric runs back and forth between a rope swing and his parents, throwing his arms around his dad’s neck and swinging like a pendulum.

Rui used to do the same with her father. She'd hang from his neck. She'd call her mother "little frog." There were no hard rules at the dinner table, no emphasis on silence and deference. Sometimes Rui overheard her mother's colleagues saying she was spoiled, but she likes to think she was lucky.

Eric wants to try the balance beam.

His mother holds one of his hands as he puts one foot in front of the other. He teeters. She encourages him but is careful not to help him too much. She wants him to be kind but she also wants him to be tough.

Psychologists have assailed Sept. 11 from nearly every angle. They’ve studied direct and indirect exposure to the event, the short- and long-term effects on both individuals and society. They’ve zeroed in on amorphous topics such as blame games, survivor’s guilt and near-misses.

They have not examined the inverse of a near-miss, nor have they extrapolated survivor’s guilt to an extreme. They have not studied someone like Rui Zheng.

Sept. 11 was about timing, and about small, everyday choices. Switching shifts with a fellow waitstaffer. Keeping a spouse at home an extra 10 minutes. The decisions of innocent people shaped the impact of the attacks. So surely there are others who made a banal choice that placed a loved one in the path of destruction. Surely there are others who feel an awful complicity, whose thoughts are routinely prefaced by “if only.”

If they’re out there, they haven’t been studied. Not that a study would make a difference for Rui. In the early days, she found comfort in the company of other families of victims. She still does. One loss is not greater than another. But she also feels separate.

“My case is kind of extreme,” Rui says with clinical reserve, as if discussing a particularly complex lymphoma. “I really don’t know how anybody could understand.”

Psychologists do study the technique of “undoing,” defined as the “continued upward comparison between reality and the better hypothetical alternative,” as it’s worded in a 1995 study titled “The Undoing of Traumatic Life Events” in the Personality and Social Psychology Bulletin.

When people imagine better scenarios, the study concluded, their reality appears especially poor by comparison.

The only time Rui spoke publicly about the full context of her case — about the “if only” — was when she was a witness in the trial of Zacarias Moussaoui in April 2006.

A photograph of her parents was exhibit No. P200295. An assistant U.S. attorney asked her to spell their names for the record.

S-H-U-Y-I-N.

Y-A-N-G.

Y-U-G-U-A-N-G.

Z-H-E-N-G.

She was asked to articulate the impact of their deaths. Her statement was not vengeful or depressive. It was penitent.

“Initially I felt like, kind of like feeling of guilty because if I didn’t change their flight ticket, everything would have turned out differently,” Rui testified. “They would still be alive and enjoy their lives. And I felt I was responsible for that. And that feeling of guilty never, never goes away. And I think that feeling will, you know, along with the trauma, be with me for the rest of my life.”

A knife slips through a long slab of pork.

The smell of steaming rice fills the house.

Rui’s in-laws patter wordlessly around the kitchen, dicing cucumbers, rinsing mushrooms, sprinkling organic soy sauce and sunflower oil into a wok. Eric is on the back deck, swishing around a bubble sword in the suburban twilight.

“I wish I was floating above in a big bubble!” he says.

“My grandson likes American food,” Li’s father says, both resigned and amused. “He eats pizza.”

Rui removes Eric’s toys from the kitchen table. Sunday night dinner. Two birthday parties down. Tomorrow, the start of another week of work, with its ceaseless flow of patient data carrying good news and bad news. Next month, preschool, with all its joys and anxieties. Next year, after her fellowship ends, she’ll look for a faculty job, which could take her away from her adopted home for the first time.

Chinese cabbage hisses on a stove.

A hemepath textbook lays open on a coffee table.

A set of loving grandparents prepares dinner.

A gold chain disappears under the collar of a blouse.

Rui Zheng has come to certain conclusions about life and the world. None are revolutionary, but they resound because they come from her, from behind an iron will, from a place that cannot be fathomed.

There are bad people who do bad things, she says, and good people who get wrapped up in it. In the end, you can control little more than yourself, she says, and what is done will never be undone. You cannot cry for years on end. You have a life in front of you, she says. Move forward, past the "if onlys." Life can stop at any second, she says, so it is precious. Think about how you should lead your life now.

She sets the kitchen table with chopsticks, nudging each pair into parallel formation.

She has come to one other conclusion: She will never have peace. Whatever’s truly in her heart cannot be identified, cannot be put under a microscope, cannot be diagnosed, studied, cured.

But focus on the pathology of life — the “Why?” — and it can kill you. So you pull back. You zoom out as far as you can, and a single day becomes a week becomes a month becomes a year becomes a decade.

You look at the whole geometry of life.

You look at Eric.

Eric, who helped his mother comprehend her parents’ own love for her.

Eric, who carries his grandparents in his veins.

Eric, on the back deck, eyes to the sky. •